Ridley Scott followed up the tremendous success of his science fiction horror film Alien with his cyber-noir thriller Blade Runner. Both films were ambitious genre expanding experiments in style and substance that inspired filmmakers for a generation but while Ripley's harrowing tale of survival on the Nostromo was a critical and box office success, Officer Deckard's pursuit of four rogue replicants in the neon dappled streets of Los Angeles of 2019, where daylight was a myth, divided critics and underperformed financially. Blade Runner would go on to sculpt a devoted audience over the course of decades, making a strong case that the film was simply ahead of its time.

Blade Runner 2049 makes that conversation much more complicated because one would think the good will accrued from the original would have crafted the steps needed for Denis Villeneuve's atmospheric sequel to ascend to the rarified air of blockbuster status. Instead, it also lost money for its studio partnerships and contributed to modest layoffs at Alcorn Entertainment. The film is considered a modern day masterpiece by most, it has spawned an animated series that broadens the worldbuilding by delving into the lore and new projects within the franchise continue in development. The reasons why this beloved property stumbles economically are complicated, but it boils down to pacing issues, somewhat unfair accusations of sexism, unrealistic financial expectations and a creative aversion to mass consumption.

The Blade Runner Franchise Runs Like A Marathon, Not A Sprint

The original Blade Runner film was remixed like an a cappella rap album, shuffled and cut through addition and subtraction more than a half dozen times. Part of the reason it enjoyed enhanced popularity over the years was because the initial theatrical release was sent under the surgeon's knife enough times to respond to either critical consensus or validate Ridley Scott's instincts. Harrison Ford always hated his voice-over narration and by the time of the Final Cut it was a distant memory. Both films are steeped in lush cinematography, whether the camera is focused on grimy damp urban labyrinths or twisted junkyard wastelands, the shots are indulgently picturesque.

At times this creates stillness in spaces where the audience craves movement. The first film clocks in at just under two hours and the second is almost three. Scott, who executive produced 2049, has admitted that he would have cut 30 minutes from the film and there is an argument that this would be a conservative trimming. Momentum is sacrificed on the altar of immersion and while the promise of flying cars haunts a generation that feels cheated of their absence, there are only so many take-offs and landings or transits through the crowded skylanes of Los Angeles that can be justified.

Sexist Tropes Abound In The Blade Runner Franchise But That Isn't The Whole Story

There are good faith discussions surrounding how women are treated in media as a whole and film in particular that are certainly at the heart of both films. No women of agency are depicted on screen in the first movie at any moment. Blade Runner features two female replicants, one was a member of a murder squad and the other was a pleasure model, but both are gunned down brutally while scantily clad. One repugnant scene between Deckard, the man tasked with hunting and murdering replicants and Rachael, a replicant who has just discovered the reality of her identity, depicts him not allowing her to leave his apartment after she decides not to go through with a romantic encounter. What follows is a subtly violent showdown where he commands her to parrot the words he wants to hear while cornering her into touching him the way he wants to be touched.

It is intended to come across as alpha male sexual conquest but instead reads as a vile and demeaning breech of the trust he is asking her to place in him. However, blaming the movie's performance on scenes such as these do not convincingly respond to other films that were released proximal to this one. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan was a certified hit from a franchise that routinely mired itself in damsel in distress tropes and the invisibility of women despite their leggy, long haired appearances. Beastmaster, Conan the Barbarian and The Best Whorehouse in Texas were all released within months of Blade Runner and the two genre pieces among them were flagrant in their caricature of women and all were more successful.

Blade Runner 2049 has its share of misogynistic pitfalls, but it also subverts them in clever ways. The doe eyed sexy hologram who lives to serve the rugged lonely synthetic cop is positioned as a precious jewel at worst and an unattainable fantasy at best. After her death the hero is left alone with a new purpose to avenge her and put right the events he has set in motion. The twist is that he is not the hero he thought himself to be, and his love was most likely an algorithm designed to make him feel special just as all of his uniqueness is stripped away. This all happens against the backdrop of strong female characters who support him in pity or try to murder him according to their own higher calling, but he is rendered as just a cog and ultimately disposable.

None of this is meant to imply that there were not other choices available to either film that would have made a more compelling story for the women who inhabited them, but it does demonstrate that their lack of ticket sales doesn't seem to align with this component as a salient factor. War of the Planet of the Apes, whose only female character was a mute child in need of protection was released the same year as 2049 and enjoyed immense global financial success.

Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 Carried Unjustifiable Budgets And Unrealistic Expectations

Juxtaposed against some of those aforementioned contemporaneous films the budget for Blade Runner was completely beyond the pale. Tron had a budget of $17 million dollars, Wrath of Khan $12 million, Beastmaster $9 million and Conan the Barbarian $20 million. Blade Runner's budget was $30 million dollars without the proven IP of Star Trek or the straight forward good versus evil plot structure that audiences find so palatable. Given how much the movie cost to make, it was always going to be a risky gamble to see a profit from a film that skipped so freely along the existential questions with no demon to bury a blade in or homicidal egomaniac to thwart.

The sequel repeated the same mistakes by spending something comparable to a Marvel film, though Blade Runner 2049 has influenced some MCU directors, and expecting Infinity level results. Originally filling out a ledger of around $185 million, the real number was decreased to a degree due to rebates and tax incentives at somewhere closer to $150 million, but given the complex and piecemeal collection of revenue for global distribution it is estimated that it would have needed to gross around $400 million to break even. Villeneuve was worried that its box office failure would doom his career, but has expressed an interest to return to this bleak landscape under the right conditions, and is clearly not lacking opportunities.

Blade Runner Hates Black And White And Has Never Cared About Being Fun

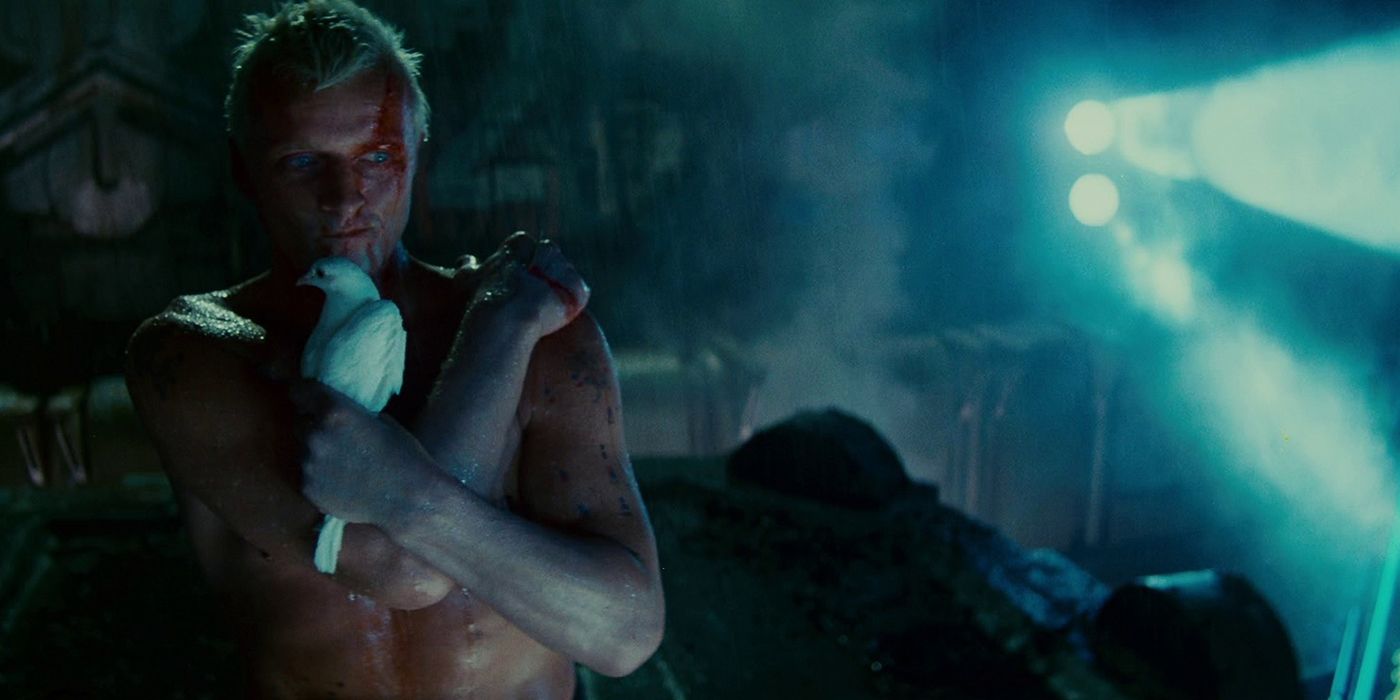

It is hard to imagine a scene during either Blade Runner film where the audience would collectively cheer at a well-earned moment of group release and descriptions of the duology as mirthless are not hyperbolic. It is instead a land of whispered awe where one takes in the sights and reflects upon them like a guided tour through an immaculately curated museum of the future featuring a dying earth exhibit. This is largely due to the fact that all the gray on screen matches the thematic thrust of any hero villain archetypes. In the first film the enemy was a group of replicants who wanted to extend their lives past the allotted four years their maker had given them. It isn't an unreasonable goal but more to the point, they are nearing their terminus as the film starts so even if Deckard did nothing they would soon die of natural causes, so what was all the fuss really for?

In the second film K, a Blade Runner replicant whose "loyalty" has to be constantly monitored, is sent to kill the unknown inaugural offspring of a human and a replicant. The antagonist is an industrialist who can't manufacture androids any quicker but would really love the boost to his stock that "natural" reproduction would provide, but he must find the child of this union to study and dissect, so he can reverse engineer the process. Depraved and dark, it still doesn't give much in the way of satisfying the appetites of the masses given all the unanswered questions and lingering complexities. These replicants do tend to go on murder sprees when they don't get what they want, but they've been so effectively anthropomorphized it seems only logical to side with them while nagging questions about their consciousness are never really satisfied. It is an effective brew, a thoughtful meditation on humanity and a vibrantly beautiful painting of a world limping toward its destruction but not a popcorn pleaser ready for easy consumption.